Celebrating the life of Dr Ronald Midgley Nedderman, 1935-2021

A profoundly influential researcher in process engineering and a source of inspiration and incalculable assistance to generations of Lecturers in the Department

It is with deep sadness that we record the death of Ron Nedderman on 18th May, 2021.

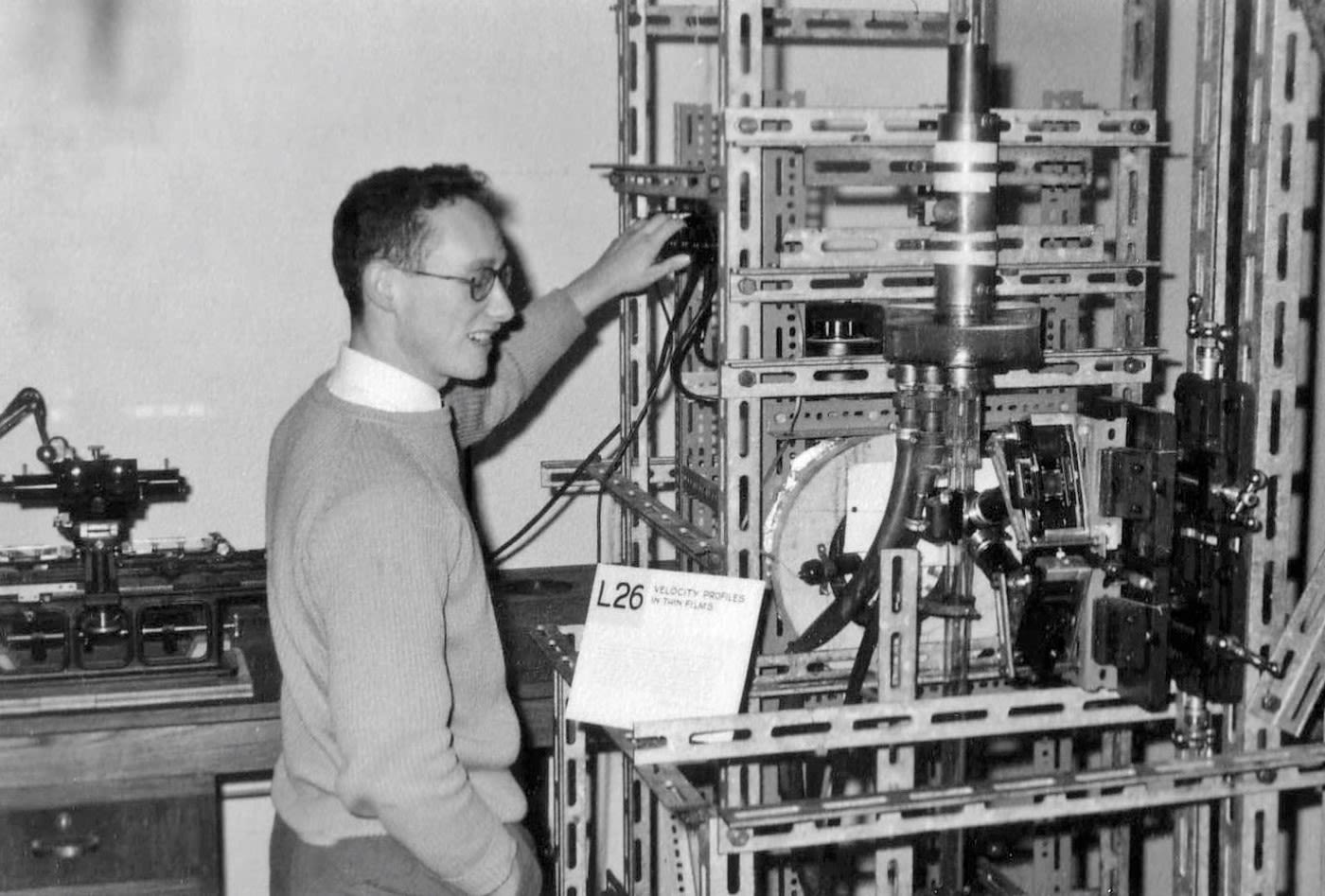

Ron was educated at Leighton Park School and came up to Cambridge to read Engineering at St. John’s. Following a First in the Engineering Tripos, he moved to the Department of Chemical Engineering in Pembroke Street and undertook a PhD, completed in 1960, on annular, two-phase flow under the supervision of J. M. Kay and, later, Terence Fox. Jim Wilkes also supervised him when Fox became ill. Subsequently, he was appointed Demonstrator and then University Lecturer in the Department, becoming a Fellow of Darwin in 1964 and then of Trinity in 1981. He retired from the Department as a University Lecturer in 2000.

Ron had a supreme intellect and was quietly and profoundly accomplished in all activities he undertook, whether teaching, examining and research in the Department or in his outside interests in botany, ornithology or Scottish Country Dancing. He is fondly remembered for his humility, generosity, friendliness, integrity and compassion. He was passionate about teaching and examining and could lecture and supervise almost any part of the Tripos with great clarity and insight. His research on two-phase flow, and later in granular statics and dynamics, was seminal and influenced profoundly the development of those important fields in process engineering. His significant advances resulted both from his intellectual insight and from his familiarity with the fundamental principles of engineering, emanating from his great interest in teaching. He was a source of inspiration and incalculable assistance to generations of new Lecturers in the Department.

In writing this obituary, I have been overwhelmed with the heartfelt contributions from so many colleagues about this most unassuming of men. I have therefore deliberately reproduced these appreciations, below, because the freshness and immediacy of these thoughts transcends the desire to try to summarise these contributions into a standard obituary.

Above all else, Ron was motivated and concerned with the welfare and education of successive generations of students. It is therefore fitting to end this introduction by quoting the words of Jamie Cleaver, a former PhD student:

"Ron accepted me as his PhD student in 1987 and was an exemplary supervisor. He guided me with patience, encouraging me to ask questions, correcting my mistakes kindly, and praising my successes. As a result, my confidence grew as my research progressed. However, it was his quiet humility and his passion for teaching that has had the biggest impact on me. Reflecting back, this quiet, unassuming man demonstrated powerful integrity, compassion, and probity, coupled with a sense of humour that would frequently catch me off guard. I recall an occasion at the start of my PhD when he directed me to one of the department support staff, whom he described as 'quiet, shy and retiring'. To my surprise, I found that quite the opposite was true. Other lasting memories include his generosity in sharing the surplus fruit and vegetables from his garden, his passion for Scotland and Scottish Country Dancing, and his encyclopaedic knowledge of ornithology. He was an inspiring role model and has been one of the biggest and most positive influences in my life."

We have all been enriched in so many ways by having had Ron as one of our colleagues. Although we saw relatively little of him in his long and active retirement, we shall surely miss him as a friend and mentor.

John Dennis

Early Years and Life at the Department

Allan Hayhurst

Ron was born in Todmorden on 7th July, 1935, in that very hilly country, where the only level field is the cricket pitch, through which the Lancashire -Yorkshire boundary passes. His family were part of the mill-owning set there. One of them made and sold Nedderman pumps for filtering the air in cotton mills. He was very much educated by aunts and grandmothers, hence his huge knowledge of botany. His mother, whom he admired, was top in Maths at the local elementary school, where Sir John Cockroft (Nobel laureate) was second. His father taught classics at Rochdale Grammar School. Ron went to Leighton Park, the Quaker school near Reading. He was much affected by Quakerism and had a collection of Quaker sayings, such as when he opposed somebody being allowed to do a job or join a committee, he would simply say “That is a name, which had not occurred to me”. That meant real opposition.

Ron went to St John’s to read engineering, without doing military service. That meant that he was two years younger than the others in his year. He became a close friend of Frank Goodyear, later the classics fellow at Queens’. They holidayed together in Greece and Italy more than once. These trips must have been very boozy, given Frank’s bibulous tendencies.

His research for his Ph.D. was supervised by Kay, who left and then Fox followed as supervisor. He worked on flooding in vertical annular gas-liquid flow. Subsequently, Fox appointed him a Demonstrator, indicating that Ron must have impressed Fox – a man not easily impressed. As was the custom then, he spent a year with Shell gaining industrial experience, which was to serve him well.

He married Susan Weller, daughter of the Bursar of Caius. She was a wonderful Scottish dancer - the best in Cambridge apparently. Their children were Jenny and Angus. They lived first in Great Shelford, later in Susan’s family home in Clarkson Road. He adored teaching and his knowledge of chemical engineering fundamentals was profound. He managed to cover nearly all the Tripos, and was lacking confidence only in chemical thermodynamics. He was very important and active when the Department started to teach a course for Part IB of the Natural Sciences Tripos. Lots of the experiments and examples sheets were his. I was one of many members of staff who benefitted from Ron’s freely and cheerfully given help, elucidating arcane bits of our course. That included providing his lecture notes. He also liked to write up his lecture notes as books and published four in total. He constantly kept an eye on what the Department taught, introducing many innovations over the years.

He became a Fellow of Darwin, and also served as an external director of studies at a number of other colleges at a time when few colleges had teaching fellows in chemical engineering. He was delighted to take a Fellowship at Trinity in 1981, when he won the Beilby prize, awarded by the SCI. Later he surprisingly enjoyed being a Tutor in Trinity; that involved Susan entertaining students. I suspect he was paid so well that he had no incentive to seek promotion. I did wonder if he had any ambition to be promoted, particularly when once I had to force him to co-author a paper with me. He could have published many more papers than he actually did.

He was interested in examining, was brilliant at it and was constantly thinking up new questions. Certainly, he taught me how to be Chairman of a Tripos and handle an External Examiner.

He was Secretary of the Department for many years, when Armstrong (in effect the HOD) ran the finance for years, without even an accounts clerk. Ron was in charge of the assistant staff and technicians. The two got on well. When I joined the staff in 1979, Ron was keen that I should take on the job. I suspect that he did not enjoy it and I acquiesced. He did not enjoy conflict.

He changed his research from working on two-phase flow to granular flow in the early 1970s, following encouragement from John Davidson and Peter Danckwerts, and from then on published seminal work on the statics and dynamics of granular materials.

For years, if you went into the Department at Pembroke Street on a Sunday morning, the place was filled with the sound of Scottish dancing. Susan was a key person in those complex circles, but Ron really enjoyed it and was interested in the dances’ structures.

Around the time that John Davidson retired, Susan’s health deteriorated, so that Ron retired to nurse her. Very sadly she died soon after that and Ron took on the life of a hermit looking after his vast garden. He had planned to write a book on grasses and also one on Scottish dances. I don’t know how they developed.

(Comment from Patrick Barrie, Director of Education for the School of Technology and University Senior Lecturer : I believe Ron completed his book on “lady step” Scottish country dances – it is apparently published as two volumes, but is not in his name. He was modest and was happy not to receive recognition for it).

Memories of Ron Nedderman

Roland Clift

I first met Dr Nedderman in 1962. I had the good fortune to have him as one of my supervisors for Part I of the Chemical Engineering Tripos and my sole supervisor for Part II. I clearly recall Part II supervisions (which were on Friday afternoons) as “ending the week on a high”. In addition to his insights into the kind of puzzle that was set as Part II exam questions, Ron introduced me to Mediaeval Icelandic literature; this was one of his passions, along with learning obscure/obsolete languages (such as Scots Gaelic), bird watching (for which he went every year to the Orkneys) and, of course, Scottish dancing. This meant that my Part II project, for which I was paired with Colin Pritchard, was carried out under Ron’s supervision. We worked on flooding points in vertical countercurrent gas/liquid flows. It led to a paper in Chem Eng Science, the first (of course) for Colin and me. Clift, Pritchard & Nedderman (1966) remains a timeless classic!

I next engaged with Ron when I was a lecturer at Cambridge from 1976 to 1981. It was regarded as commonplace for staff to attend each other’s lectures (we were expected to provide supervisions on the material, after all) so I attended Ron’s on granular materials and the method of characteristics – two subjects that can be notoriously perplexing. His ability to bring clarity to complex topics again made these lectures something to look forward to. It took a lot of persuasion, from many people, for him to turn his clear grasp of granular materials into a book, although that finally happened in 2005.

Ron had been a Fellow at several Colleges which he described to me as “unsatisfactory” but, after I left Cambridge in 1981, he became a Fellow of Trinity College (where I had been a Fellow and John Davidson was a prominent figure – Vice-Master for a while). Ron then immersed himself more in the College and became a Tutor.

I suppose the picture this conjures is of Ron as a Cambridge eccentric, but that wouldn’t really capture the man. I think he had decided that his world would be defined by the statutory “Within 10 miles of Great Saint Mary’s Church” and wanted to be significant on his own terms within that world, without much interest in what happened outside it. He succeeded on those terms, but I think you needed to “experience” him at first hand to know what a remarkably clear intellect he had, and also what a very nice man he was.

Testimonies from colleagues

In his first term as a Demonstrator on the first day of lectures, Ron told me he was in the Department expecting to give his first lecture later in the week when he was ushered into the lecture theatre at 9 am and told to hold forth for 50 minutes. Whether this was a timetabling mistake or staff illness, I did not ask. He had no notes but kept going to emerge relatively unscathed. As a student you knew you had raised a really good query if Ron had, on a very rare occasion, to respond with one of his favourite phrases “I require notice of that question”, which meant he needed a week to research the matter and think about it, which he would do very, very carefully. He was one of those that saw the Department through tricky times to viability. The tricky times included student numbers in the small category such that very few colleges had chemical engineering fellows. John Davidson knew his true worth and will have been instrumental in persuading Trinity to make him a Fellow. Ron famously never went to a research conference in the time I knew him. I don’t know exactly why; he sent research students like me instead which showed confidence in us and his thorough input to the paper to be given.

John Davidson always referred to Ron as the star of the scholarly teaching dons whose output came in the form of excellent textbooks rather than a long list of research papers. It might be, in today's climate, that he would have received more recognition through promotion, but he never appeared to be discontent. It meant of course that a tutorial and supervising role at Trinity fitted him better than a Fellowship at Darwin. His steady commitment to the Department's teaching and administration (rather like Denys Armstrong’s) was an enormous help to the Department generally - not least other academic staff who could take their sabbatical leave in faraway places like the USA and Australia! He was devoted to bird-watching, and I believe that included regular visits to the Farne Islands.

I am grateful to Ron for helping me as a beginner in Chemical Engineering - he held my hand in the IB NST Fluid Mechanics Lab, he gave me his resources for the IB NST and Part II Fluid Mechanics lecture courses, and he suggested a topic for a Part II research project and how to run it. Over the years, and after his retirement, Ron gave me helpful advice in variety of other areas too, including granular materials and thermodynamics. His knowledge of Old Schools folk came in handy from time to time.

I would also like to echo the generous eulogies to Ron. I can recall him 'interviewing' me when I first visited the Department in 1979. He showed genuine interest in my experimental research flow pattern photographs that I showed him and was just 'a really nice person'. Ron also really knew his Chemical Engineering and I continually referred to his book on fluid mechanics which formed the backbone of the then Part1B second year Natural Science option course. I also recall at some stage Ron saying ‘we’ (that is the staff of Chemical Engineering) should stick to teaching what we know best. He certainly followed that path and was a fantastic teacher of fluid mechanics and granular materials. Ron was highly respected by all the staff and importantly by the students. He was a brilliant Tripos question setter and also examiner, something that he took very seriously.

Just to add my appreciation of all that Ron did for the Department over many years. He was very patient with me as a new arrival in the Department with absolutely no knowledge of chemical engineering (early 1980s). It was never too much trouble for him to explain to me some point in a mathematical proof that I was having trouble with. He tried, unsuccessfully I fear, to persuade the young University Lecturers to prepare their draft exam questions for next year early, by his always setting his whilst invigilating that year's Tripos examinations. Invigilation was a task that fell to all academic staff in bygone years. I very much doubt whether any exam question he set ever had an error or ambiguity in it; it was very much his forte. I always remember him wearing a light blue pullover, grey trousers and open sandals with socks; a man of habit I think.

Indeed, Ron was a great teacher and an excellent researcher. I remember going to an international particle technology conference (held in Disney World, Florida!) – in one session every speaker referred to Ron’s work! Ron played a very important role in creating the Department we have today.

I was an undergraduate in the Department and was supervised by Ron for two years. His knowledge of the Tripos was formidable and he had the gift of posing questions so that the students could identify the key points in a problem and develop a solution without denting their confidence too much. I have passed the news on to several colleagues from my early years and they have echoed Howard's point about Ron as a colleague, mentor and friend. It did take me some time to get used to his addressing me by my 'first' name rather than 'Wilson' - he always addressed undergraduates by their surname, which was commonplace then. In later years, Ron concentrated on teaching but was not inactive in research: his last PhD student, Dan Horrobin, conducted leading edge research in FEM modelling of extrusion of viscoplastic pastes. Dan's dissertation won the Danckwerts Pergamon prize and is a model document. This, however, is not surprising: Ron was sometimes heard to say 'My dissertation was reasonably good: I have helped to write some really good ones since'. Ron was a keen botanist, with a particular interest in British plant life. He was quoted as having chosen a career as a professional engineer and amateur botanist as the finances worked out better that way. Talking of finances, Ron spent a year as a young lecturer working for Shell: he remarked that in those days a university lecturer had a higher salary than an engineer of similar age at Shell.

Ron was my Director of Studies back in the 1990s and was a fantastic supervisor. I owe him hugely for teaching me.

I remember discussing some issue with a lecture that I was having and his replying that he considered that lectures were the second worst way to impart information and knowledge – I wonder what he would have made of the educational delivery over the past year! Oh, and for those wondering what he considered the worst way to impart knowledge? That was the method that Gulliver found on his travels when he visited the Academy of Lagado in the land of Balnibarbi. There, students were required to inscribe (using “cephalic tincture“) a proposition on a wafer and then swallow the wafer. A subsequent fasting for 3 days would cause the proposition to fix in the brain.

Ron was my mentor when I moved across from industry to academia and I owe him a lot. He was also a great friend and I was very sorry when he retired completely. I still use his book in my supervisions and I am sure that most of the fluids example sheets were his work.

Ron genuinely enjoyed interacting with students and conveying knowledge to them. He was less keen on University, Department or College politics. He was quietly knowledgeable about many things, be it unit operations, varieties of lichen, or types of moth. He had his mannerisms and pet phrases – he frequently said “quite so” when he agreed with something said. He always had a twinkle in his eye when making a remark designed to elicit a particular response. He sometimes struggled with advances in computing, always preferring the satisfaction of physical insight where possible. I remember him looking perplexed over a laser printer one afternoon that was producing reams of output – he had accidentally requested 20 copies of a document, rather than a single copy of page 20, and didn’t know how to stop it. Ron’s wife, Susan, and he ran Scottish Country dancing in Cambridge for decades – both within and without the University. After Susan died, Ron remained active and he was still holding dances in his Cambridge garden each summer until he moved out 2 years’ ago.

What else can I add to all these deserved plaudits to dear Ron, whom I first met on joining the Department in 1964? Yes, he was always very modest, extremely generous with his time and knowledge, as well as being an acute observer of all going on around him. It was very easy to underestimate him.

In memory of Ron Nedderman, 1935-2021

© Trinity College Cambridge

© Trinity College Cambridge