High speed super-resolution microscopy records driving force of cellular protein factories

Researchers from the University of Cambridge have identified the driving force behind a cellular process linked to neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and motor neurone disease.

In a study published today in Science Advances, researchers from the Cambridge Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology (CEB), show that tiny components within the cell are the biological engines behind effective protein production.

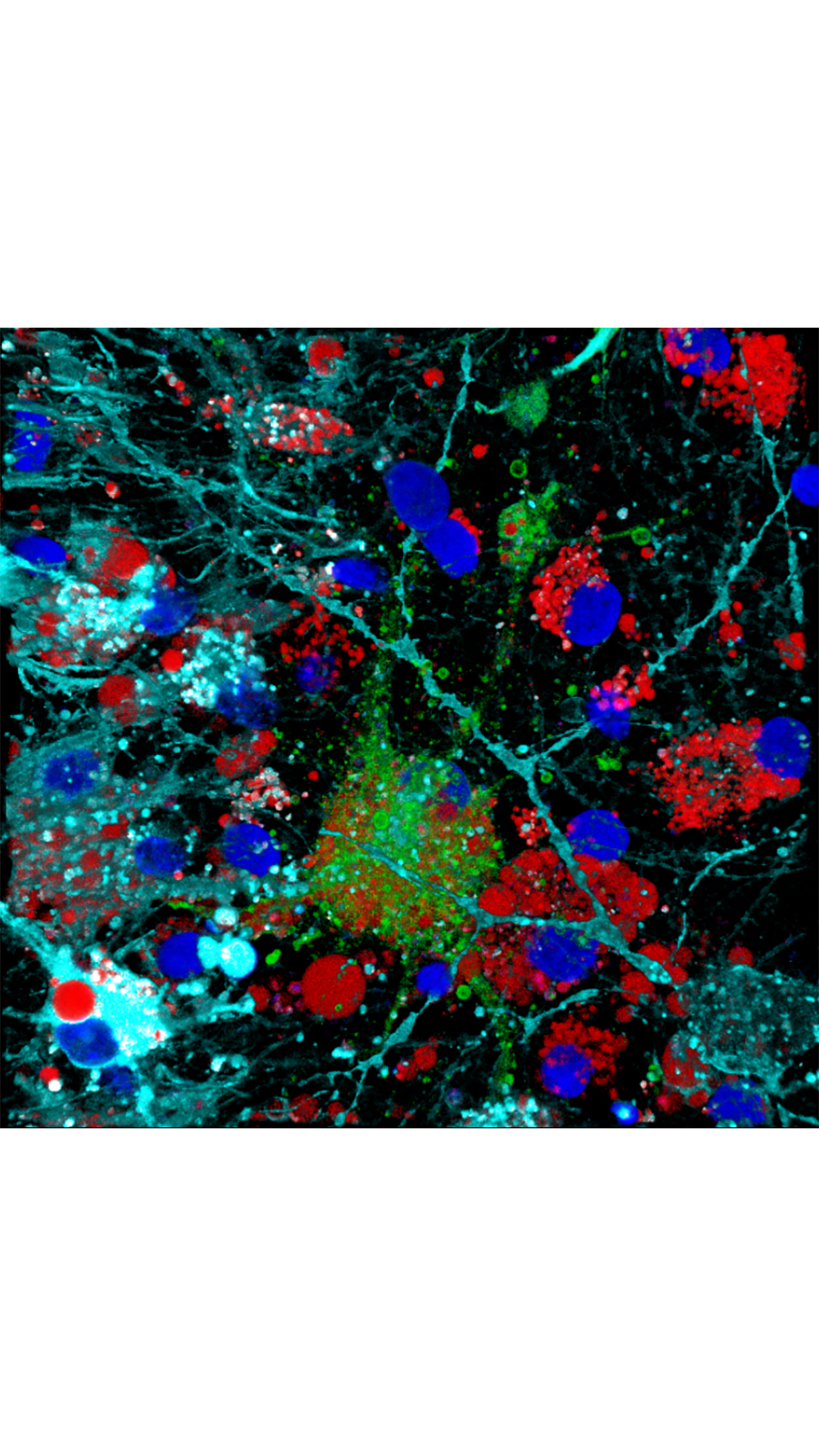

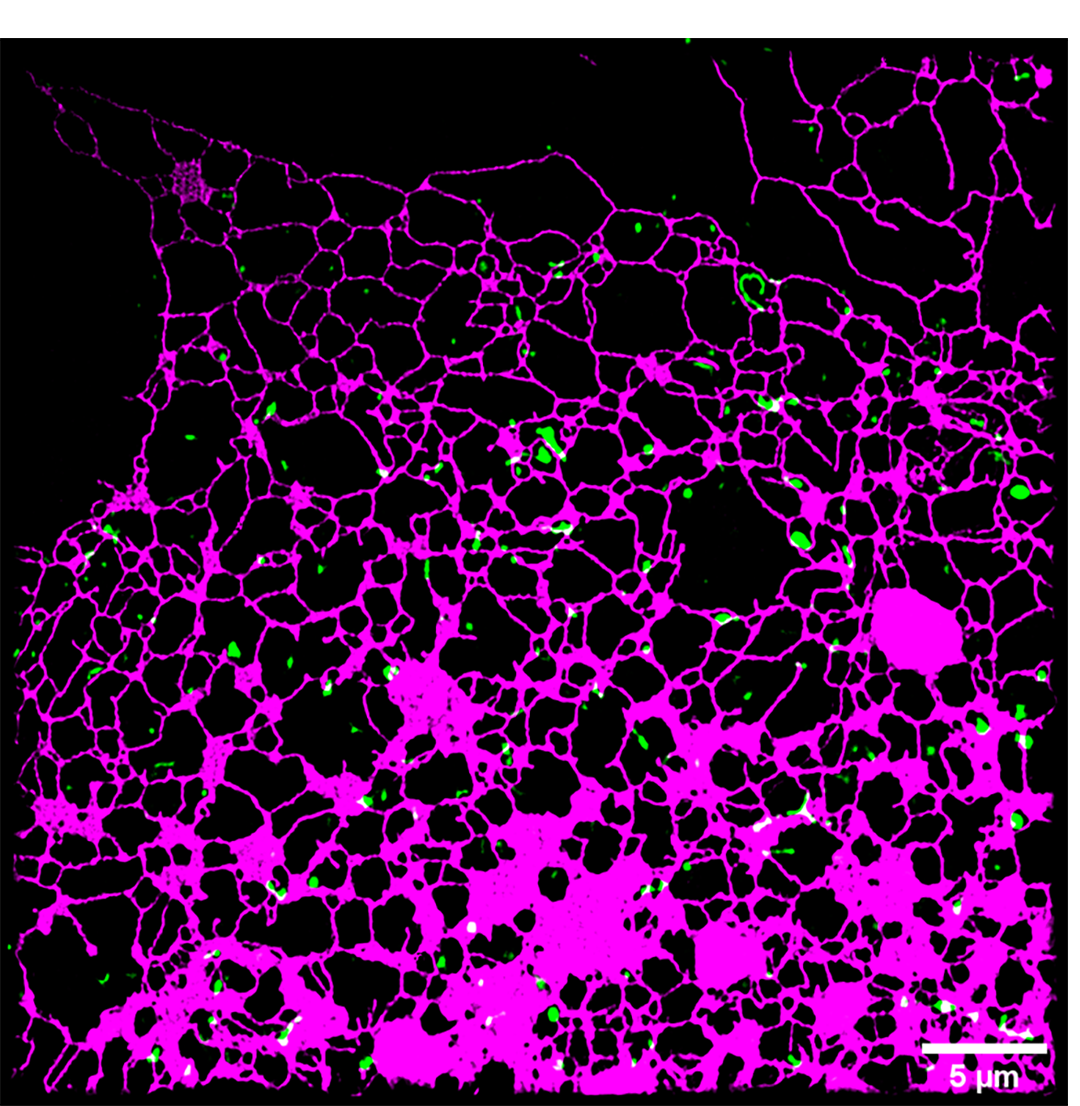

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the cell’s protein factory, producing and modifying the proteins needed to ensure healthy cell function. It is the cell’s biggest organelle and exists in a web-like structure of tubes and sheets. The ER moves rapidly and constantly changes shape, extending across the cell to wherever it is needed at any given moment.

A representative image of ER network (magenta) and its close contact with lysosomes (green).

A representative image of ER network (magenta) and its close contact with lysosomes (green).

Using so-called super-resolution microscopy techniques, researchers from CEB’s Laser Analytics Group have discovered the driving force behind these movements – a breakthrough with significant impact in the study of neurodegenerative diseases.

“It has been known that the endoplasmic reticulum has a very dynamic structure – constantly stretching and extending its shape inside the cell,” explains Dr Meng Lu, research associate in the Laser Analytics Group, led by Professor Clemens Kaminski.

“The ER needs to be able to reach all places efficiently and quickly to perform essential housekeeping functions within the cell, whenever and wherever the need arises. Impairment of this capability is linked to diseases including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s and ALS. So far there has been limited understanding of how the ER achieves these rapid and fascinating changes in shape and how it responds to cellular stimuli.”

Lu and colleagues discovered that another cell component holds the key – small structures, that look like tiny droplets contained in membranes, called lysosomes.

Lysosomes can be thought of as the cell’s recycling centres: they capture damaged proteins, breaking them down into their original building blocks so that they can be reused in the production of new proteins. Lysosomes also act as sensing centres – picking up on environmental cues and communicating these to other parts of the cell, which adapt accordingly.

There can be up to a 1,000 or so lysosomes zipping around the cell at any one time and with them, the ER appears to change its shape and location, in an apparently orchestrated fashion.

What astonished the Cambridge scientists was their discovery of a causal link between the movement of the tiny lysosomes within the cell and the reshaping process of the large ER network. “We could show that it is the movement of the lysosomes themselves that forces the ER to reshape in response to cellular stimuli,” explains Lu.

“When the cell senses that there is a need for lysosomes and ER to travel to distal corners of the cell, the lysosomes pull the ER web along with them, like tiny locomotives.”

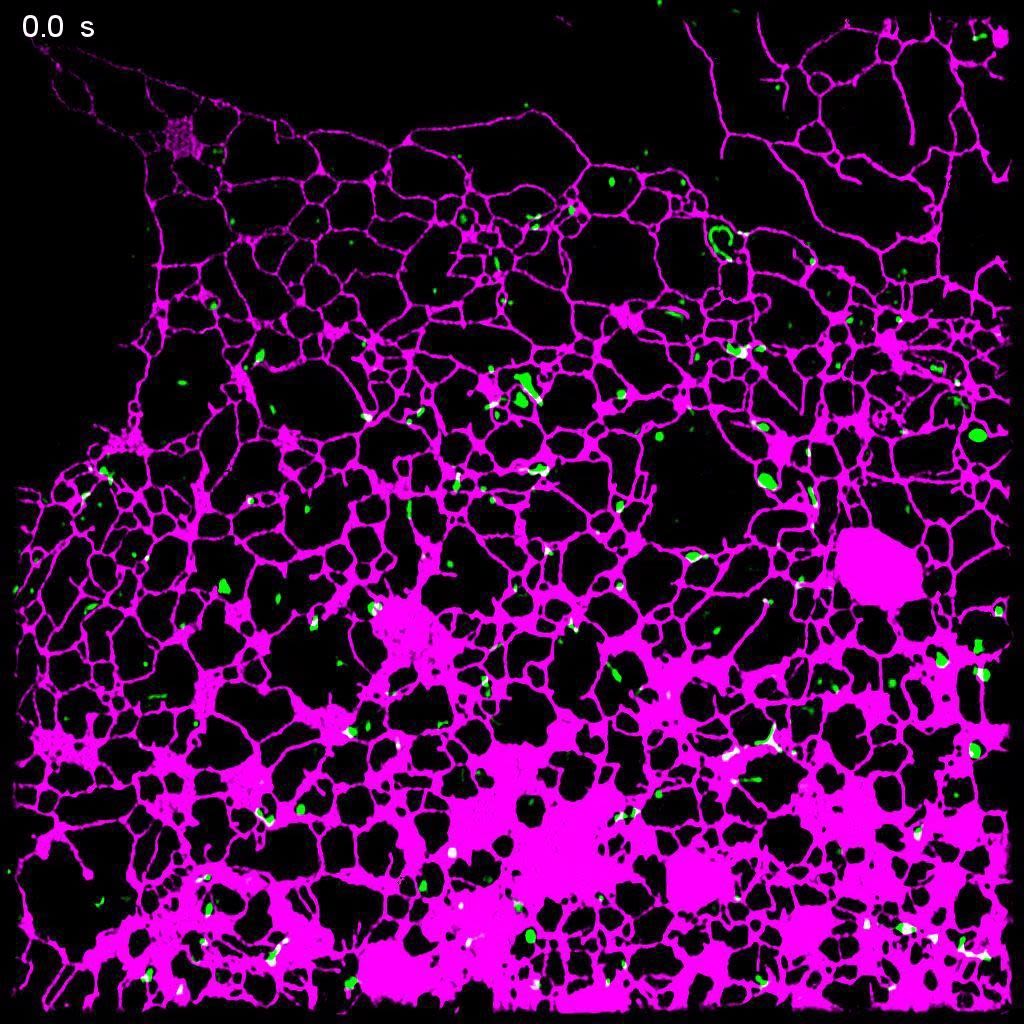

Live cell super-resolution imaging demonstrates the ER network (magenta) is undergoing constant dynamic reshaping, which is coupled with lysosomes (green).

Live cell super-resolution imaging demonstrates the ER network (magenta) is undergoing constant dynamic reshaping, which is coupled with lysosomes (green).

From a biological point of view, this makes sense: The lysosomes act as a sensor inside the cell, and the ER as a response unit; co-ordinating their synchronous function is critical to cellular health.

To discover this surprising bond between two very different organelles, Kaminski’s research team made use of new imaging technologies and machine learning algorithms, which gave them unprecedented insights into the inner workings of the cell.

‘It is fascinating that we are now able to look inside living cells and see the marvellous speed and dynamics of the cellular machinery at such detail and in real time,” says Professor Clemens Kaminski. “Only a few years ago, watching organelles going about their business inside the cell would have been unthinkable.”.

The research group used illumination patterns projected onto living cells at high speed, and advanced computer algorithms to recover information on a scale more than one hundred times smaller than the width of a human hair. To capture such information at video rates, has only recently become possible.

The authors also used machine learning algorithms to extract the structure and movement of the ER networks and lysosomes in an automated fashion from thousands of datasets.

The team extended their research to look at neurons or nerve cells – highly specialised cells with long protrusions called axons along which signals are transmitted. Axons are extremely thin tubular structures and it was not known how the movement of the very large ER network is orchestrated inside these structures.

The work by Lu and team explains how: lysosomes travel easily along the axons and drag the ER along behind them. The researchers also show how impairing this process is detrimental to the development of growing neurons.

A representative recording of a lysosome (green) pulling fragmented ER (magenta) to connect and maintaining ER continuity in a growing axon.

A representative recording of a lysosome (green) pulling fragmented ER (magenta) to connect and maintaining ER continuity in a growing axon.

Weakening the affinity between ER (magenta) and lysosome (green) leads to failed elongation of ER and an increase of velocity of lysosome.

Weakening the affinity between ER (magenta) and lysosome (green) leads to failed elongation of ER and an increase of velocity of lysosome.

Fascinatingly, the researchers frequently saw events in their images where the lysosomes act as repair engines for disconnected or broken pieces of ER structure, merging and fusing them into an intact network again. The work is thus highly relevant for an understanding of disorders of the nervous system and its repair.

The team also studied the biological significance of this coupled movement, providing a stimulus – in this case nutrients – for the lysosomes to sense. The lysosomes were seen to move towards this signal, dragging the ER network behind so that the cell can elicit a suitable response.

“So far, little was known on the regulation of ER structure in response to metabolic signals,” says Lu. “Our research provides a link between lysosomes as sensors units that actively steer the local ER response.”

Inducing lysosome (green) anterograde motion with light leads to a rapid and significant extension of ER network (magenta). The images were reconstructed by (CNN (convolution neural network) based image segmentation.

Inducing lysosome (green) anterograde motion with light leads to a rapid and significant extension of ER network (magenta). The images were reconstructed by (CNN (convolution neural network) based image segmentation.

The team hopes that their insights will prove invaluable to those studying links between disease and cellular response, and their own next steps are focused on studying ER function and dysfunction in diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Neurodegenerative disorders are associated with aggregation of damaged and misfolded proteins, so understanding the underlying mechanisms of ER function is critical to research into their treatment and prevention.

“The discoveries of the ER and lysosomes were awarded the Nobel Prize many years ago – they are key organelles essential for healthy cellular function,” says Kaminski. “It is fascinating to think that there is still so much to learn about this system, which is incredibly important to fundamental biomedical science looking to find the cause and cures of these devastating diseases.”.

Read the full paper, published in Science Advances

The structure and global distribution of the endoplasmic reticulum network is actively regulated by lysosomes

Meng Lu et al.

10.1126/sciadv.abc7209